|

Distillers — Legal...

Distilling, one of Derry's oldest industries, once ranked as a

leading employer of labour in the city. At the beginning of the last

century, there were three distilleries in the city, and one in the

parish of Clondermott, which in the year 1835 produced 19,000

gallons of spirit. Of the city's distilleries, Smyth's at

Pennyburn had an annual output of 39,000 gallons, and the

Abbey Street or Bogside distillery produced 44,000 gallons. Its

joint owners were Mr. Ross Smyth and Mr. David Watt.

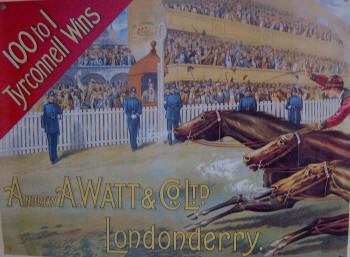

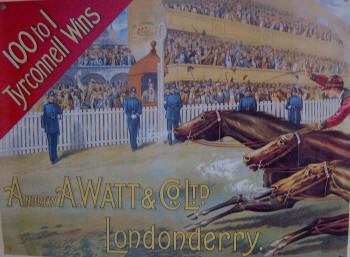

The Watt Family, which hailed from Ramelton, were the pioneers and,

for a century and a half, the mainstay of the industry. Most of the

Derry whiskey was exported to America, though the local market was

considerable, despite the profusion of poteen stills that flourished

in its hinterland. In 1833, there were 175 spirit licences in the

city, catering for a population of 18,000.

In the heyday of the whiskey trade the censure that was later

accorded to excessive drinking was not yet in evidence, for a report

of the typhus epidemic in 1817 lists a supply of Pennyburn among the

donations from "the benevolent gentry" to the victims, who were so

numerous that they were accommodated in tents in the grounds of the

fever hospital.

Though some outside observers dwelt on the prevalence of drunkenness

in the city, the Press did not consider it worth reporting;

prosecutions for drinking or the making and selling of poteen and

theological disputations were far better "crack."

The author of the Ordnance Survey (1835) roundly berated the better

paid workers, such as coachmakers and tailors, but offset his

picture of a boozy proletariat by mentioning the city's 500

registered teetotallers, whose only recorded activity was attending

tea parties. However, as the century wore on, there were reams of

drink cases, often involving the major traffic offence — drunk in

charge of a horse or donkey.

The Pennyburn distillery closed in 1840 and the 50 men and boys

employed there moved to Abbey Street, where the pot stills were

replaced by the new patent stills, whose inventor, Mr. Aenas Coffey,

came to Derry to supervise their erection. The work force further

increased and the distillery became one of the best known in the

United Kingdom when Old Tyrconnell superseded Pennyburn.

Possibly the emigrants took the taste with them for it dominated the

American market; early films of major baseball games show the

Yankees Stadium ringed with hoardings extolling Old Tyrconnell.

The Waterside distillery, which was owned by the Meehan

family, of whom the last was Recorder of Derry, passed in 1870 into

the control of Mr. David Watt. It closed in 1902 when it was

amalgamated into United Distilleries Group, but the name was

commemorated in the recently demolished Meehan's Row.

A mass closure of Irish distilleries followed the First World War

owing to high taxation and decreased consumption and, what was

particularly telling in the case of Watt's, the loss of the American

market with the introduction of Prohibition. In 1921, the Abbey

Street distillery closed, and distilling became another extinct

Derry Trade.

...and illegal...

On a map drawn for

the purpose of a Revenue Commission in 1836, Derry and Donegal are

shown as the principal centres of the poteen industry in the North

of Ireland. "Illicit distillation can scarcely be said to exist

south of the Liffey or the Shannon" the report stated. In that year

in Derry City there was 174 spirit licences and 165 for beer and,

the report went on, "the public houses are of different degrees of

respectability; in some of the inferior type gambling prevails but

all are useful in diminishing the number of unlicensed houses and

checking the sale of illicit spirits which is very extensive and on

the increase."

The heyday of the poteen industry was about 30 years earlier, just

after the Union; in 1815, when whiskey was selling for 9s. 6d. a

gallon, the Excise duty was 6s. 11d. So heavily penalised was the

legal trade that poor quality materials made it unpalatable, and

many local stills were forced out of legal business. the risk of

detection determined the mode of distribution. In Derry City, during

the period of the Napoleonic wars when the Excise forces were

directed to coastal defence garrisons, poteen was sold in open tubs

in the street.

Twenty years later it was supplied by turfmen, who hid kegs under

their loads, or small operators, ostensibly selling eggs or butter.

Yet there were many who could afford "parliament" whiskey but

preferred the "craythur" for its flavour and potency; only a

degraded palate, it was held, could tolerate the taste of smoke in

preference to the "hogo" of turf — but they were not sufficiently

numerous to form a specialist market. Production reached its peak in

these years, for nearly two-thirds of all spirits consumed in

Ireland were poteen. The government retaliated by recruiting an

excise force of 1,000 men, who, within two years, seized 16,000

stills. Evidence was also given at successive Commissions, that

amateur distillers were frowned upon by big operators, like the man

near Derry who was in such a way of business that, "He is the only

man of his sort who eats white bread, toasted, buttered and washed

down with tea for his breakfast."

Success so striking must have called for exceptional qualifications,

chief of which would inevitably be an aversion or well bridled

fondness for his own products — only teetotallers make successful

publicans. But the Inspector-General of the Excise was sceptical and

told the enquiry that he never knew anyone engaged in the making or

traffic in poteen who grew rich by it. The social risks were often

formidable; one harassed distiller complained, "As soon as it is

known that I am making a run, every idle blackguard for miles around

considers it neighbourly to drop in and drink my profits."

Next to Derry and its hinterland as poteen centres were Bun an

Phobail (Moville) and Magilligan Point, but, when a Revenue cutter

began patrolling the lough, those markets wilted. The Royal Irish

Constabulary who took over from the older revenue force were much

more successful in suppressing the traffic — they were reputed never

to use snuff, the better to smell out poteen — but it was the

imposition of spiritual penalties that led to the disappearance of

of stills and shebeens in the North-West. Harassed by Church and

State, the stillers' products deteriorated and, dependent on the

least stable of the community, passed into folklore. |